- Home

- Gaby Koppel

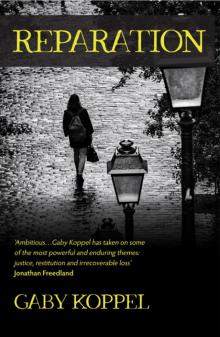

Reparation Page 3

Reparation Read online

Page 3

“Let me see…”

“Andrew, for God’s sake, you’re not in the dorm any more playing pranks.” A deep red patch is gnawing its way up his neck, towards his bumfluffy chin. He takes out a card and reads out the name of a detective inspector at Stoke Newington police headquarters, then adds, “He’s a jobsworth. You’ll be wasting your time. ”

As I walk away, Susannah points at Andrew and mouths the word “wanker” to me. But the truth is, I need this story to come good after my idiotic performance just now. When I get to my desk, my notes are there, lying on top of a pile of old newspapers and looking a lot grubbier than last time I saw them. Six stories with all the relevant crime details, meticulous lists of witnesses and contacts for police officers in charge of each case. And, not leaving anything to chance, a list of any previous contact the programme has had with them. I crumple the sheets into a ball and hurl it at Andrew’s empty desk. But it falls short and skids across the carpet tiles.

Before I phone Hackney Police, I call my father.

“Dad, there’s something I need to ask you.”

“Ja. What is it?”

“You know the other day, when Mutti went missing at the airport?”

“Mmmm.” He doesn’t want to talk about it.

“It’s not about that. Why on earth was she going to Ibiza by herself anyway?”

There’s a silence on the other end of the line. I can hear paper being moved around, and computer keys being pecked at. He sighs.

“We are selling the flat.”

“What?”

Their little piece of paradise, they called it, immune to the concept of cliché in any language. It was their sanctuary in the sun, a two-hour charter flight away from strangulating, foreigner-phobic, England. I remember when they bought it, long before the island became the ultimate clubbing destination. Up at the back of San Antonio, on the quiet streets where the town starts to rise into the hills. It was second home perfection; two beds and a balcony on the Med. A little bit of their beloved Continent that was going to be forever theirs. And the subtext – unspoken of course – somewhere to run if the fascists ever emerge from the political margins. Gone.

They must be desperate for cash if they’ve sold up. So, how bad are things? Are we talking bailiffs? I picture their house in Rhiwbina as it was when I last visited. The house I grew up in, all its teak and leather furniture was still be there. I think. I can’t convey any of this to my Dad. It’s unsayable. He would feel more relaxed about dropping his trousers in public than discussing his finances with me. I whisper, “Oh.” I want to ask how bad things are. Tell me honestly. Except it just won’t come out like that.

“But where will you go?”

“Holidays we won’t have for a while. Not necessary.”

He makes it sound like a minor detail of a business deal. Which makes me suddenly feel very tender towards him. I click down the receiver cradle, and when I hear the dialling tone, punch in the number for Stoke Newington Police.

Chapter 3

The following weekend, my folks come down to London for a family party. In preparation for their arrival, I’ve poured away that half bottle of Rioja we had left over. If Mutti just happens across a stash of drink, the weekend will be wiped out while she’s snoring on the sofa. So, out of consideration for my father, the rest of what we like to call “the wine cellar” has been stuffed in the wardrobe. Côtes du Rhône with my sexiest lingerie and two very nice Pinot Grigios nestling in the murky depths of my Russell & Bromley boots.

We’ve agreed that we’ll meet at Dave’s place, but I’m running late. At six o’clock I’m still in the office waiting for a phone call from the officer in charge of the Stamford Hill murder. I’ve spoken to him every day, and he still hasn’t agreed to put me in touch with the dead girl’s family. Now he’s “locked into a meeting” again, and I’m phoning every five minutes to make sure he hasn’t left for the day. Pestering it may be, but I don’t dare to face Sarah tomorrow without a result.

I call Dave. Of course my parents arrived as Big Ben chimed six, their Germanic instinct for punctuality overriding not just the build-up of weekend traffic on the M4, but also a three car pile-up on the Cromwell Road. Dave’s playing host. Even though we’ve been going out for two years, I’ve managed to keep them apart pretty successfully until now.

“Don’t worry,” he says, “I’ll look after them.”

“Are you sure?” My parents will take a dim view of my poor timekeeping. No business deal or important meeting ever stood in the way of my father getting home pünktlich each evening at seven. By now he will be pacing up and down the bare floorboards, while my mother’s looking round the loft and wondering out loud why Dave doesn’t have fitted carpet. Then she’ll ask (again) why we aren’t living together.

Mutti loves to advertise her liberal credentials, and that includes actively encouraging me to do what was once called living in sin. She’s so keen to be modern or as she would say “with-it”, that she doesn’t realise the only person she’s liberating is herself. I spent my adolescence dodging her chummy one-to-one chats about periods. I didn’t want to discuss sex with her when I was sixteen, any more than I want to discuss why I’m not living with Dave now.

“It’s cool,” says Dave. “I’ve taken the lemon vodka we bought in Moscow out of the freezer. We’re having a few shots before dinner to celebrate. We can tell them our news then.”

I don’t hear the last part of that because I feel as though someone’s just put a bullet through my chest. My mother is downing “a few shots” with Dave. Will she go AWOL in Islington, and be found asleep on a park bench with her handbag round her neck? Dave doesn’t get it about my mother and drink. Yes, I have moaned to him about her antics, but he insists on seeing this all as the eccentric yet harmless behaviour of a colourful Hungarian émigré. Somehow it’s never been quite the right moment to spell it out to the man you want to marry that you are the daughter of a dangerous drunk. But surely he could have cottoned on by now?

I know what he’d say – a few bevvies, what’s the harm in that? He’ll be shocked when he finds out. He’s not had my years of training. I am Coping Strategies Central, and my bleeper is going off right now. I’ll have to put off my pursuit of Inspector Jenkins till tomorrow, even if it means facing a bollocking from Sarah. I race down to the basement car park and drive off, jerking my way through the gears. The Westway is four lanes of solid, stationary hot metal suspended over Notting Hill, and I’m trapped in my baking car, with raw sulphuric acid burning a hole in my stomach lining.

By the time I get to Dalston High Road, my blouse is glued to the centre of my back. I stand in the street and look up. What will the folks have made of this, I wonder? It’s hardly the red brick, three-bed semi that is their concept of residential bliss. It isn’t even a house, or really a flat in the accepted sense. It’s a vast, crumbling loft, rented out at a subsidised rent for use as a workshop-cum-studio, on the explicit understanding that no one lives there. I ring the bell. There’s a pause, and the sound of Doc Martens on stone stairs before Dave answers, beaming.

“Is everything OK?” I whisper.

“Yes sure, why not? Why are you whispering?”

“Well, giving her neat vodka could be a bit like…”

“She’s not like anything. You exaggerate. Let the poor woman have a couple of drinks, for God’s sake. I gave them a guided tour of my palatial studio facilities and a look through my portfolio.” He winks.

The entrance to the studio is guarded by a life-size illuminated plastic statue of Madonna and child. My parents will have been startled to see that as they arrived. They may think they are sophisticated Europeans, but irony’s been deleted from their list of functions. It’s only a matter of time before they start wondering out loud whether Dave attends Mass.

We wind our way between the freestanding clothes racks that serve as a wardrobe, and a medley of second-hand furniture that’s been artfully arranged to form rooms. The effect i

s charming/a complete mess – delete as appropriate depending on your own personal taste in interior design. And I know what my folks would think of it. Pretty much the same as they think of Dave.

As I peer through the forest of paraphernalia heading for the part of it which serves as a kitchen, I see that Dave has misjudged the situation. The shot glasses are scattered all over the table. Two of the mannequins have fallen over and are skewiff on the floor on top of each other, their pith helmets scattered around, still rocking. They look as though someone’s tried to mock up a sex scene using dummies, like some weird pornographic art installation. My father looks preoccupied as I kiss him hello. Mutti is red in the face, her polyester knit top askew, dark sweat patches creeping outwards from the armpits. I brace myself as she gets up to greet me, but after a cursory hug, she turns back to Dave.

“Come on, we aren’t finished.”

I scan the room, looking for the bottle of vodka. Surely they haven’t drunk the lot? Dave takes off his denim jacket and sits down at the kitchen table opposite Mutti. I see her registering the tatts. They’ll only confirm her view of him as a bit of a yob, but she cans that one for later. Now it’s time to get down to business. They fix eye contact with each other, alpha male against alpha female, put opposing elbows on the table, then lock hands. She was never much of a one for small talk so instead she’ll challenge a bloke of any age to beat her at arm wrestling.

There’s a lot of heaving and huffing. As a much younger man, he should win easily, but bulk is in her favour. She may look all very genteel, but lurking behind that triple string of pearls is a pair of shoulders built by years as a swimming champ, tennis player and all-round athlete. Maybe one of the reasons she survived years of privation is that she’s got the constitution of an ox, and though she barely lifts a finger these days, she’s still incredibly strong. It’s infuriating. By the time we get to the Italian trattoria in Islington, she’s beaten him by four rounds to three and they are buddies.

Though we order some more wine with the meal, Mutti’s on her best behaviour. In fact, both my parents are on top form, telling all their best anecdotes about being a foreigner in Britain after the war. The absence of civilisation broken only by the blessed relief of having German-speaking shop assistants at Woolworths in Swiss Cottage and the ancient story about my uncle in the Home Guard, lost on manoeuvres near Merthyr – a fat man on a bicycle wearing a British army uniform and speaking with a thick German accent. This and more is brushed down and whirled out for Dave’s benefit.

The good thing is that it means there’s very little time left for my parents to probe Dave’s professional activities and finances. What a relief. They’d never understand how many years it can take to get one’s work seen by the right people. Eking out an existence on the dole while he draws together his portfolio is unlikely to impress.

My efforts to steer the conversation away from those delicate areas pays off. My parents have forgiven Dave for not being a Jewish lawyer. After all, he laughs at their jokes and has a healthy appetite, and that’s nearly as good. But they think he is just another in a long line of boyfriends. Possibly because I made it known several years ago that I was “never getting married”. I did that to stop my uncles and aunts asking every single man I ever brought home whether he was going to “make an honest woman” of me, as though I was a career criminal not a television researcher.

As the dessert arrives, everyone is relaxed. Too relaxed.

“So, David, what are you doing with these photographs?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Are you selling them? Putting in a magazine?”

Dave laughs, as though Mutti has cracked an amusing joke.

“When the portfolio is complete, they will go into an exhibition, in one of the good galleries,” I say. Dave looks surprised, but nods. “Somewhere like the Photographers’ Gallery, or IKON,” I add.

“That would be great, of course,” he says, sounding mystified. It can only be a matter of time before Mutti asks him how much he earns. You have to be born British to understand just how impossible that question is.

“And at this exhibition, you sell the pictures?” I see this question for what it is. A warm-up to the main act.

“Actually,” says Dave, “that’s not really the point.” Now it’s my parents’ turn to look baffled. “You see, the point is to create work with integrity and meaning like any other artist would. I don’t think Degas or Van Gogh or Picasso set out thinking ‘how much can I earn from a painting’.” There’s a lot of nodding round the table, and I’m pretty certain Mutti is checking out Dave’s ears, to make sure they are well attached to his head. Dad is probably thinking well, at least Picasso made a few bob.

“So,” says Mutti, “how much would you charge for one?”

“Well…”

“Two hundred pounds,” I say, trying to sound blasé.

“That would be very nice…” says Dave.

“Or guineas?” suggests Mutti.

“You are getting it mixed up with Sotheby’s,” I say, with a touch more acid than I’d intended.

“Very good,” says Dad. “Two hundred for just a photograph. A snap. Maybe I should sell some of the ones I took in Ibiza. Ha ha. And how many do you think you would sell in one show?” This is offensive to Dave’s artistic sensibilities in so many different ways.

“It’s not really about the money, Dad,” I say.

“No?”

“As Dave said, it’s art.”

“But a photograph isn’t a work of art like a painting. We can all take a photo. Click, there you are.”

“Er, not quite as simple as that. I thought Dave showed you his studio and dark room?”

“But painters spend years, they learn the technique, perspective, colour, all this.”

“And Dave spent two years at the Royal College of Art.” He nods. Anything with Royal in it works for my parents. However dubious they may be about this country and its impenetrable Establishment, their belief in the royal family and everything associated with it remains inviolate. But my darling father is not above calculating the pecuniary value of Palace associations.

“So, this means you can charge more for a picture? Good. How many do you think you sell from this exhibition?” Any moment now, and he’ll be asking for the date.

“How about some coffee?” I ask, waving my hand over-enthusiastically at the waiter, to create a diversion. I make a big production number out of the relative merits of cappuccino and filter coffee, and a pantomime of considering an Irish coffee, even though I know that none of us are really interested in anything other than a double espresso. Then I excuse myself from the table, stopping only to whisper in Dave’s ear.

“I’m just going to the loo. Can you come out there in a moment, I want to tell you something.” He makes a face at me, but a few minutes later we are squeezed together in a corridor.

“I don’t think we should tell them tonight,” I say.

“Why not? I’ve got them eating out of my hand.”

“My folks can be – unpredictable.” He looks worried, so I add, “They do like you, that’s absolutely true. They think you are great.” I kiss him. “But maybe we should talk about it just once more before we go ahead and share it with them.”

“We’ve got to tell them some time. Preferably before the wedding.” He’s beginning to get annoyed.

“All I’m saying is it doesn’t have to be right now.”

“I don’t know what you’re so worried about. They’ll be thrilled, believe me.”

Dave returns to the table while I go to splash cold water on my wrists and brush translucent powder on my shiny nose. When I get back they’re all grinning at me, and the waiter is opening a bottle of sparkling wine. The cat is out of the Louis Vuitton handbag.

“Mazel tov, darling,” says Mutti as I sit down at the table.

“Are you sure you are OK about this?” I whisper to her.

“What do you mean? You are engaged aren’t

you?” There’s a worrying note of desperation here. Maybe after waiting so long for me to get hitched she’s lowered her standards.

Many years ago I raised her hopes when I told her that my first serious boyfriend’s father ran a soft furnishings shop in Golders’ Green. She was half way to booking the caterer by the time she realised that he was the only non-Jewish trader in a mile–long stretch of the Finchley Road. A public school background and baffling enthusiasms for cricket and jazz, meant that First Serious Boyfriend was holed under the water. Even without the beard. My mother is single-minded in her disapproval of facial hair.

And tennis is the only sport she acknowledges. Back in the day, she adored Rod Laver and Jimmy Connors, who therefore paved the way for general acceptance of Indian tennis professional boyfriend, and his impeccable door-opening-for-ladies manners. My parents tried to put the most favourable possible gloss on the situation by emphasising how much Indian people are like Jews. They have, my father repeated many times, the same family values. The thing is, they are like Jews. But they’re not. Our parents met, on a single excruciating occasion, when his mother described in loving detail, a journey over the Him-aa-lia mountains. My parents nodded. But I could tell they were mystified about this exotic location.

By the time Dave comes along, most of my cousins are married, the bottom drawer Mutti has been putting by for me is now full of moth-eaten treasures. A compromise is on the cards. I pull her away from the table, and towards the cloakroom.

“Well, you know Dave’s not…” I glance round at him, but he’s sharing a joke with my father.

Reparation

Reparation